Search this site ...

Tribal art

What do we define by 'Tribal Art' (also known as Ethnographic art) ?

As the name suggests, it is just that: art born from settled farmers and hunters; tribal communities that often had their own autonomy and therefore their own characteristics. These arts, rooted in cultural context are governed by a set of rules that are as complex as those that govern Western art forms.

Tribal African art is probably the hardest of all tribal art to interpret given that we are talking approximately three thousand ethnic groups spread out across an entire continent!

African tribal art

Decorated knives

Decorated knivesZimbabwe and Congo

African tribal art consists of wood carvings, (masks and sculptures), stone carvings, furniture, ceramics, metalwork, jewelry, basketry, textiles, pipes, musical instruments, weapons, beadwork and the production of architectural features like doors and wall decoration and construction.

Not all of the tribes practiced all these art forms, the development of certain crafts being due to the availability of raw materials, knowledge and skills. Wood was the most frequently used material, often embellished by clay, pigments, shells, beads, ivory, metal, feathers, animal hair and raffia, and sometimes even semi-precious gems.

Particular cultures had particular histories and particular skills development and practice. Art was integrated into every aspect of life from formal ceremonies and religious rite to daily household tasks. It reflects the cycle of life; from birth, through initiation to adulthood, to death, to becoming an ancestor.

The term 'tribal' may make us think of an inferior form of art, associated with primitivism and thereby presuming lack of sophistication of skill, design, intent or concept.

Yet tribal art is enjoying more and more of the world's attention as museums are re-evaluating and re-curating their collections in recognition of the fact that it is far from crude and primitive and very often shows a skill of execution that is way beyond what we expect. It also has the power to make a connection to our souls: Perhaps by their strong presence and their emotional dynamism, our inner instincts are brought to the surface and we connect with their veracity, nourishing our lack of something; a spiritual depth, a sense of something missing.

Tribal artifacts are indeed fascinating objects that have conjured up deep emotions not only for the tribal people for whom they were created but subsequently, also for the people who came into contact with these pieces.

Many of these artifacts left African shores in the 1800's when travelers and then missionaries, took them back to their own countries as objects of curiosity. Not all of the emotions experienced were pleasant; fear, distaste, even repulsion and disgust. These feelings were generally evoked though a lack of comprehension on the part of the observer but it's not to say that becoming informed changed one's perspective!

While one can possibly view this dispersion of African art in a disconsolate light, it has meant that these items have ended up residing in countries where the rigors of harsh climate and termites have not affected them adversely.

Effectively they been preserved for us to now appreciate and enjoy.

Within their own communities, since the artists themselves attached primary importance to the function for which they were created and not their aesthetic value, it meant that they were not venerated as pieces of 'art', with a monetary value attached. In migratory tribes they also had to move with the seasons and suffered damage, were lost or abandoned.

Ngumoi mask, Tribal art, University of Iowa

Ngumoi mask, Tribal art, University of Iowa Singe nkishi sculpture

Singe nkishi sculptureDRC Tervuren museum

Fully understanding tribal art from an observers' viewpoint demands a deep appreciation and knowledge of Africa's history and cultural background. To know what one is looking at, to be able to appreciate the innate qualities of that object upon which one is gazing, requires in-depth study and a desire to comprehend something that is generally out of our realm of experience.

Tribal carving is executed for a clear and specific function. A mask may be carved to be used by a shaman in a ritual ceremony or dance; a figure may represent an ancestor or used to purposefully invite favour with the gods and spirits.

A post may be carved as a totem or as a fence post or a prop for a chief's house. A chair may be intricately carved to represent the authority of a chief or king or a head rest smoothed, rubbed and refined for a night's sleep. A walking stick or pipe is given undue attention of detail and significance according to social scale.

The more dramatic and skillfully worked the piece can be fashioned, the purer it is in intent and the more it achieves its purpose of function.

The oldest sculptures and masks that exist today for observation were created in the late 17th Century such as those that reside in the Tervuren Museum in Belgium whose collection of Central African art numbers close to 250 000 pieces of sculpture, masks and ceremonial furniture brought to Belgium by government officials and missionaries. Most of these pieces date from 1890 to 1940.

Historical tribal areas

- Sudan - Bongo

- Ethiopia - Ababa, Addis

- Somalia - Merca

- Western Sudan and the Guinea Coast

- Dogon tribe of central Mali

- Bambara of W Mali

- Baga of NW Guinea

- Poro, Dan of Liberia

- Baule, Guru, Senufo of Cote D’Ivoire (the Ivory Coast)

- Ashanti, Dahomey of Ghana

- Nigeria - Nok, Yoruba, Benin

- Igbo, Ibibio, Ekoi and Ijaw of SE Nigeria

- Cameroon and Gabon - Mangbetu, Bakota

- Republic of Congo Kongo

- Bateke, Bapende of W Congo

- Bembe, Bushongo, Basonge of Central Congo

- Baluba of SE Congo

- Chokwe of S Congo

- Zaire and Angola - Luba, Songwe, Hemba

- Angola - Katanga

- Kenya - Kamba, Giriama, Turkana

- Tanzania - Jiji, Makonde, Maasai, Mbulu

- Mozambique - Makonde, Chemba, Bisa, Noyonanyonga

- South Africa - Zulu, Nguni, Tembu, Shangaan

- Zambia - Rotse, Lozi, Tonga

- Zimbabwe - Shona, Ndebele, Venda, Shangaan, Tonga

- Namibia - Herero, Yei, Himba

Modern African Tribal Art

In modern terms, tribal art is difficult to qualify as such because while a contemporary African artist may acknowledge his tribal roots and pay allegiance to it, very frequently he/she may no longer live in an isolated, self-directed community situation but rather has become part of modern day society, frequently living either abroad or in urban societies.

Contemporary African artists often use aesthetic form to express a societal comment on the impact of urbanization and globalization on their culture. Their art can reflect this while still assimilating traditional skills and tribal culture and beliefs into their work.

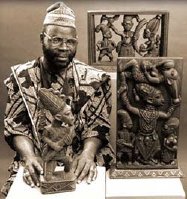

Lamidi Olonade Fakeye, Nigeria, 1925, died Xmas 2009.

An eminent and celebrated artist whose middle name 'Olonade' means 'the master artist is among us' or simply 'the carver is here', depending on whether one sees him in an elevated status or not.

Either way, Fakeye is internationally recognized for being a carver who is a modern master of the ancient Yoruba tradition of ONA wood carving.

He produced his first piece at 10 and thereafter bought an imperial quality to his creations which spoke volumes about the culture of his tribe and all its myths and folklore.

Sometimes styled in solid panels, in relief or in figurines and working in his preferred medium of iroko wood, he had particular themes he developed; Oduduwa, Olumeye and House Posts.

His work was also often used as part of architectural aesthetics in the tradition of decorating palaces, public institutions and homes of the elite who recognized the sustainability and value of the continued practice of majestic wood carving.

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.