Search this site ...

African patterns

An ode to my profession...

Africa has a wealth of patterns, everywhere you

look you will see repetitions of shapes and colours, textures and lines laid out in all

sorts of arrangements.

So what is so interesting about patterns?

Besides being so visually appealing, I see pattern making in Africa as an innate thing, akin to rhythm: The pounding of maize in a bowl feels the same as the stamping of pigment on fabric..... the weaving of hair braids is the same soft rhythmic exercise as plucking at an mbira.

Take a drive anywhere in Africa and look for patterns; note the decorated houses, see how the road stall is set out in product groupings defined by colour or shape. Look at the woman across the street... see the woven, patterned basket she carries on her head, observe the colourful, printed or dyed fabrics used to clothe her.

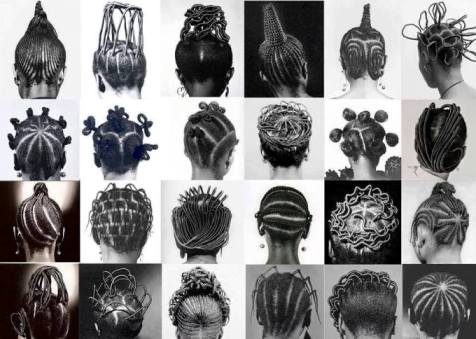

Notice the precise, rhythmic rows of her hair braids, sometimes intricately decorated with their own recurring patterns.

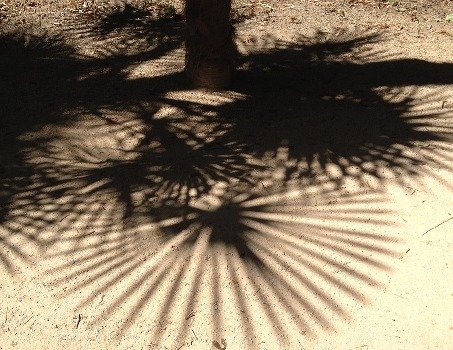

It seems to me that these photos of textures in the sand could be reflective of those braids.... or the other way round?

In nature, and all around us in Africa, there are patterns that can be visualised or conceptualised. On the land, observations of botanical items like leaves, trees, thorns, pods and seeds reveal elegant shapes, lines and patterning. Deeply thrown afternoon shadows from trees and rocks lend themselves to beautiful intricacies of pattern. So, too, do the camouflage markings on animals, birds and insects.

Deep river waters make whorls and eddys and at the ocean, waves create textures in the sand. Sea shells and fish have beautiful intricate patterning for adornment and coral creates crazy outline shapes. So much reference to use as a source!

Palm shadows

Palm shadows basket patterns

basket patternsThe fan of palm leaves in shadow remind one of the spread out fan shapes seen both outside and within these round, woven placemats.

Observe all of these details, overlay a sense of rhythm and you will find repetition of form and shape (patterns) ..... in everything!

zebra patterns

zebra patternsProduced in Zimbabwe, these original and unusual mosaic tables featured above have used both animal, reptile and geometric sources for the Africa-inspired, Africa Collection.

Palm trunks

Palm trunks Palm frond

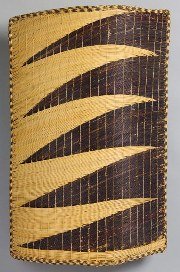

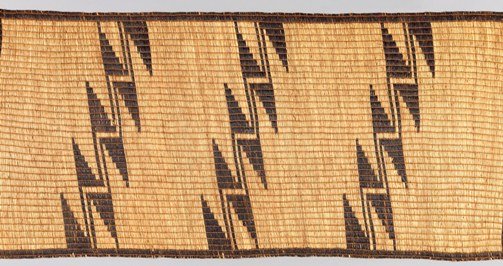

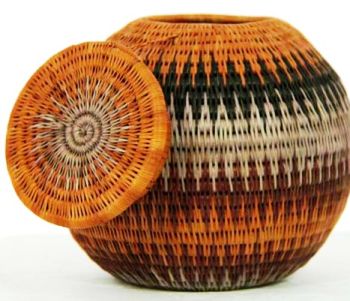

Palm frondTutsi basket patterns seem to me to have been derived from palm trees, either the fronds or the markings on the stalks which occur rhythmically at intervals.

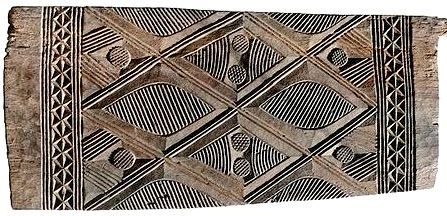

Tutsi screen

Tutsi screenPattern styles and motifs may change from culture to culture, providing insight into personal style and culturally specific aesthetics.

Add meaning to some of the symbols, colours and shapes used in various surface effects and you have a complicated and challenging topic to explore to any level you care to!

Types of Pattern

These generally fall into 2 groups:

- Geometric - Linear and organic: Diamonds, triangles, lozenges, triangular or square chequerboard, parallel zigzags, chevrons, dots, circles, curved lines or waves, spirals

- Symbolic - Natural or man-made representative motifs: Includes cruciforms, crescents, stars, mosaics, flowers, fruit, seeds, pods, trees all used emblematically.

Symbols are visual expressions of a society's culture; its philosophy, beliefs and history. They may be rich in proverbial meaning and often signify the collective wisdom of the tribe. They can communicate knowledge, feelings and values and therefore play an important role in Africans' concept of reality.

They can depict anything from animal and human behaviour to important events, or they can simply reflect their environment and various aspects of their lives in shapes and emblems.

Some are quite literal in their translation but others are representative, not representational.

Even if its a recognisable shape like a palm tree, there will be meaning behind its inclusion in a pattern and what it adorns. For example, like the palm tree which represents self-sufficiency but is used to highlight the notion that human beings are the opposite - that they are not self-sufficient!

Common patterns

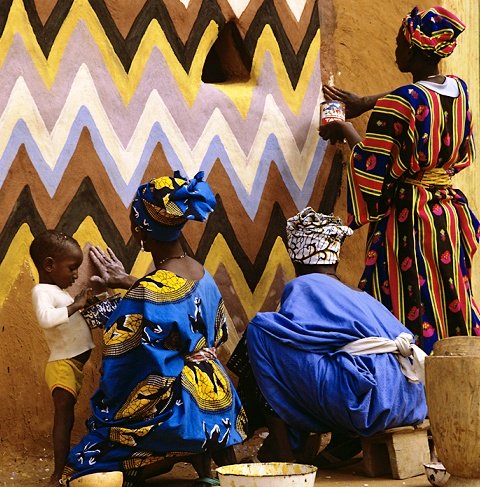

Parallel zigzags reminds the viewer to obey the 'path of the ancestors', often used to represent the fact that nothing in life is straightforward and the path will be difficult to follow.

Chequerboard black and white triangles, or squares, represent the separation of knowledge and ignorance. White represents the beginning of process of learning and black, the accumulation of wisdom.

An example of where symbolic motifs and emblems are vigorously used are by the Ashanti tribes of Ghana and the Gyaman of Cote D'Ivoire who apply motifs to fabric, pottery and paper - visual representations of concepts and idioms.

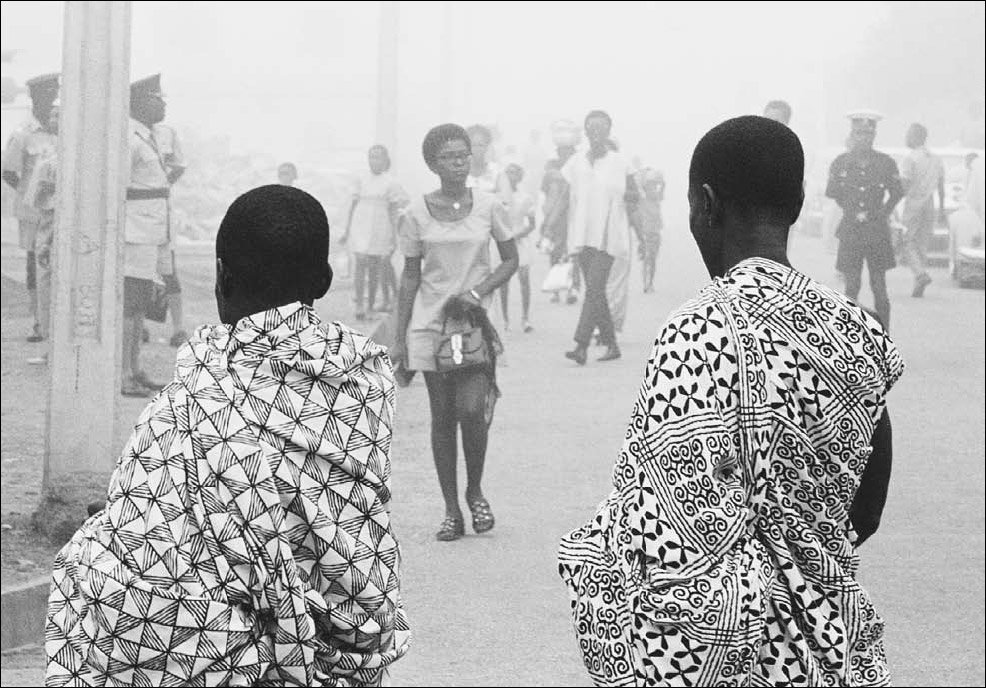

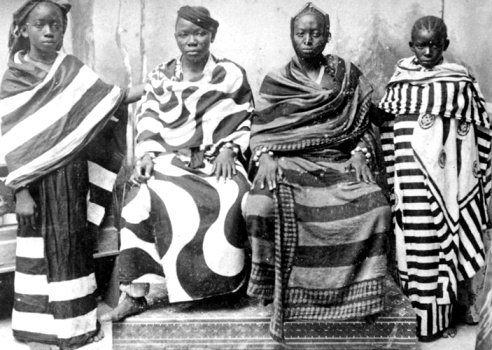

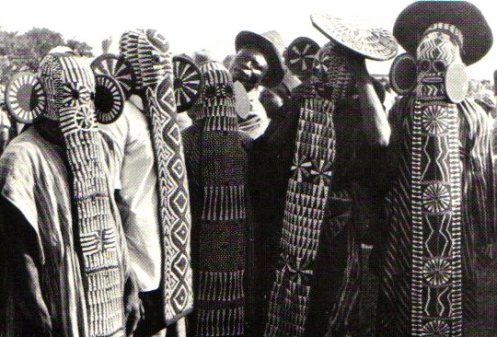

Adinkra robes, seen here below worn by two Ashanti men, are stamped with motifs in various patterns that have symbolic significance and tell a story or recount a proverb.

The important thing to remember is that they are constantly evolving and new influences in current societies are reflected in new motifs.

Being aware of, and having understanding of the nature and function of symbolism as a form of communication in both current and historical cultures will help provide understanding of the pattern of thoughts and feelings of contemporary African cultures.

History of pattern

Our main source of historical information about African pattern and design comes from architecture, decorated artifacts, masks and textiles.

The style of patterning on architectural ruins and remains can give us significant insight into the building and the occupational history of a construction.

Historically, many forms of mathematical geometric variations have occurred in both repetitive border and all-over patterns.

Chevron stone pattern, Great Zimbabwe

Chevron stone pattern, Great ZimbabweChevrons and zigzags exist in just about every form and facet of African decoration.... like in the wall structures of the ruins of Great Zimbabwe or the Asante stool seen above.

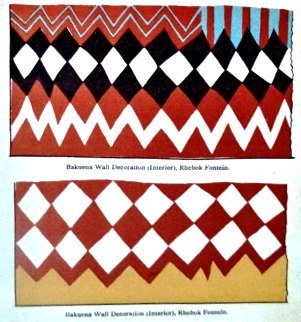

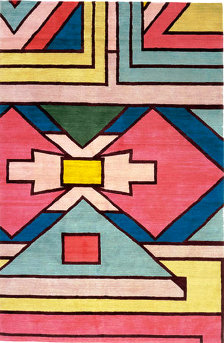

Geometric shapes of diamonds and triangles are probably the most common shape for use in a multitude of ways; painted, incised, scraped, embossed, printed, embroidered... you name it. Arranged repeatedly in vertical or horizontal rows, they can be interchanged or scaled up or down for dramatic effects like the pattern below.

1905, wall-decoration, SA-patterns

1905, wall-decoration, SA-patterns "Mali', colour 'dune', Hertex fabrics

"Mali', colour 'dune', Hertex fabricsHere, an antique document recording wall patterns from 1905 is used as a resource for a contemporary African textile design.

Sadly, in this modern era, a lot of the meaning and historical significance of various shapes or motifs is lost to us and can only be conjectured about.

But in some cases, like it is with Adinkra printed cloth or Kente woven cloth, the meanings of the selected colours or motifs used in the pattern have been passed down from generation to generation. The symbolic connotation is meaningfully applied by the artist... and comprehended by the wearer.

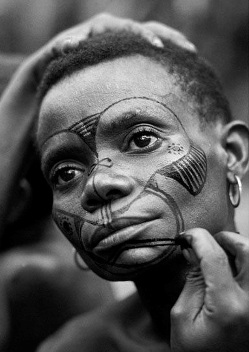

The style of patterning on the garments, robes, body wraps and aprons that adorn certain tribes can also give us significant insight into their social and religious backgrounds.

The women of East Africa took plain white slave cloth as a blank canvas for embellishment, creating hand-painted variations which were often strongly patterned to make a social statement and elevate their status.

Like in the old photographic print below, the garments often featured bold designs executed in a black, paste-like paint that was mixed from natural sources like barks and roots, black soot and coconut oil. Motifs were generally derived from recognizable images, mainly plant (like the cashew nut-the paisley shape and associated with wealth) or graphic geometrical shapes making for extremely striking apparel.

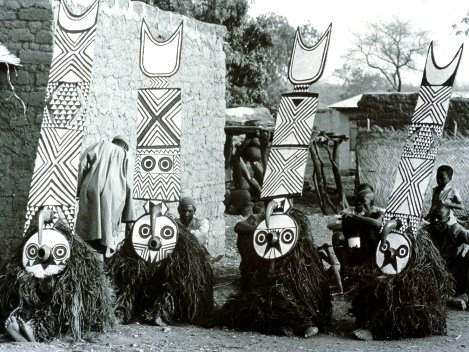

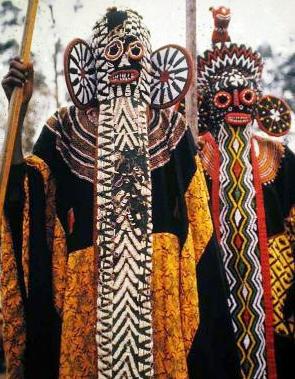

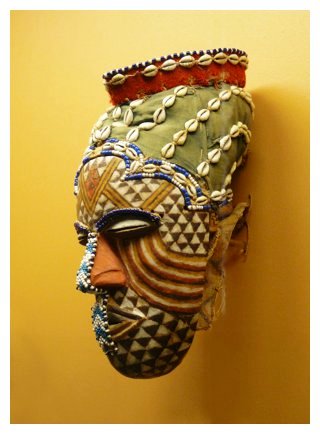

Bold pattern either painted, embellished, carved or etched is a powerful and expressive component of African mask design. Most patterns tend to be geometrical and symmetrical and often provide distinguishing marks for identifying whether the mask is male or female.

Patterns on masks and textiles were used as a form of identity for tribes and outsiders could be easily identified if their masks and robes were foreign to the area.

Use of patterns

All over Africa there is an overwhelming sense of design and an underlying structure of consistent and recurring pattern.

Patterns are used in the decoration of:

- Architecture-walls, roofing, doors, columns, finials, tiles, ceramics

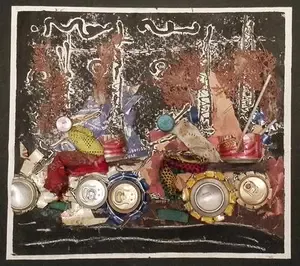

- Functional objects-baskets, pottery, furniture, musical instruments

- Adornment-jewelry, amulets, hair, combs, body painting and scarring, tattoos

- Artifacts-carved, painted, embellished (beaded, cowrie shells, seeds, pods,metal, leather)

- Textiles-woven, printed, tie-dyed, stamped, embroidered, sewn on, appliqued

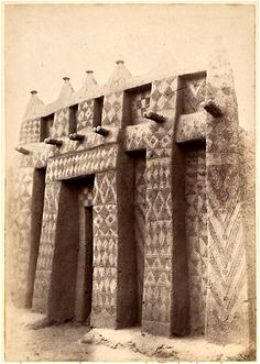

Architecture

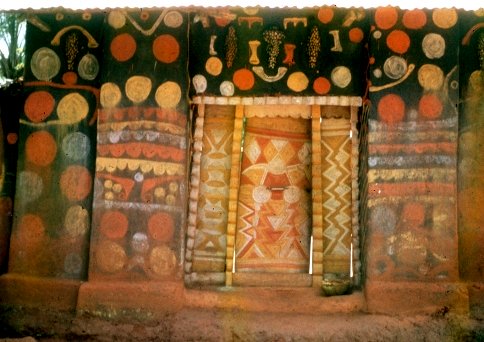

Portal-Ozo, Igbo, 1966

Portal-Ozo, Igbo, 1966The building to the left shows design decoration both painted and in relief. The other image shows an unusual painted circle design and decorated doorway from the Igbo tribe, circa 1960's.

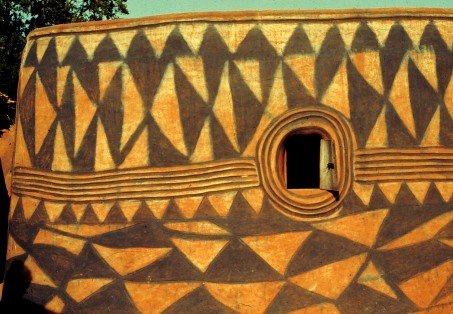

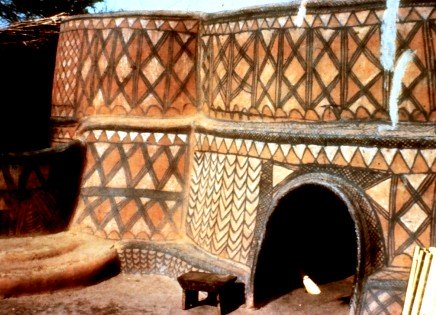

Painted wall, Frafra home, N Ghana

Painted wall, Frafra home, N GhanaThe solid Adobe houses above are from Northern Ghana.

The Frafra people paint their traditional Gurunsi mud houses with strong geometric patterning along with constructing undulating walls, curved doorways and circular windows making for an intriguing looking dwelling!

The Ndebele women of Zululand, NW South Africa have been decorating the walls of their houses and compounds for generations- a tradition called ukugwala which showed their design ability as worth of a good wife.

In the 18th C they painted their walls with their fingers, dragging them through wet clay plastered on to the wall surface to create undulating or straight lines in geometric groupings.

The complex murals of today only started relatively recently in the 1940's when Ndebele women began to have access to commercial paints.

Ndebele mural designs can communicate information about a family's history and identity.

The most vividly coloured patterns had the same style as that seen in their beaded jewelry, aprons and other utility items.

Artifacts & Craft Items - functional and non-functional

Beaded items

Cache-sex or female beaded aprons show exquisite designs and patterning. The geometric elements are beautifully arranged in sophisticated combinations of both shapes and colours.

Baskets

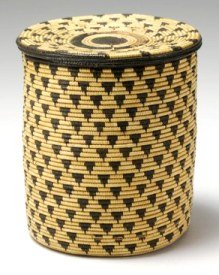

Botswana, Tatham Gallery

Botswana, Tatham Gallery Wall of baskets, floral design, Zim Nat Gallery

Wall of baskets, floral design, Zim Nat GallerySome basket patterns have evocative names like "Running Ostrich', 'Snake Stomach', 'Wings of a Bat' and 'Ribs of a Giraffe'.... also 'Forehead of the Kudu' or 'Forehead of the Zebra'.

'Running Ostrich' is also known as the marks made from a bicycle tire... in modern times it is hard to know if the names of the patterns have carried down the line with their meaning intact or if they have been re-interpreted.

Carved Items

Doors, headrests, walking sticks, combs, boxes are all items that lend themselves to detailed carving and decoration.

Headrests exhibit very personal style since they are such individual used objects but they also have design elements that are repeatedly used throughout Southern and Central Africa - especially the ndoro (the concentric circle motif that bears reference to the base of the white conus-shell, a valued status symbol).

Other motifs used like the triangles, keloids and chevrons bear reference to the scarifications which were traditionally exhibited on both African males and females.

Some artifacts are incised with relief carving like the Shona headrest and some have carving as well as being masterfully sculpted into 3 dimensional forms like both the stools above.

Masks

Most designs on masks tend to be geometrical and symmetrical. Mask patterns can denote social status and have magical or spiritual powers. Patterns are combined to convey the rules for proper conduct in the tribe and the requirements of the spirits that the masks represent and are therefore a powerful form of communication.

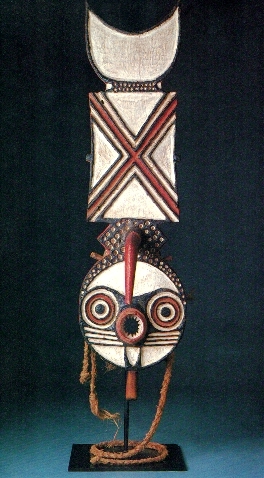

Bwa mask, Volta region

Bwa mask, Volta regionColour can determine regional and tribal characteristics and styles.

The Voltaic people of Ghana apply red, white and black colors to their masks in intricate geometrical patterns with symbolic significance..... as do the Bamileke of Cameroon.

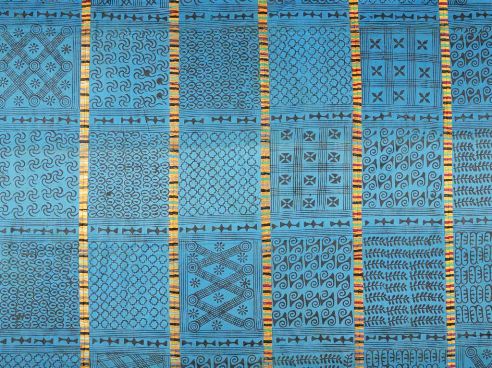

Textiles

Of all the genres by which patterning is exhibited in Africa, textiles carry the most exciting and most complex form of repetitive design.

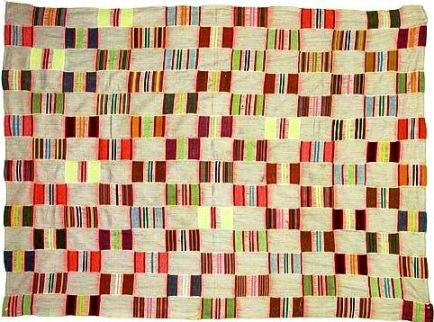

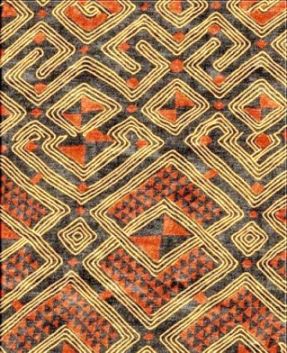

Kente or Ashanti cloth from Ghana has over 300 different traditional patterns. As the cloth is woven in strips and then sewn together, the design possibilities for a finished piece are endless.

Kente quilt

Kente quiltBoth the use of color and the selection of motifs or symbols will have their own connotations and, of course, different combinations of these will say different things in a pattern. Usually there is more than one color and one pattern found in a single piece of fabric but sometimes, it can be just one with a particular message to get across.

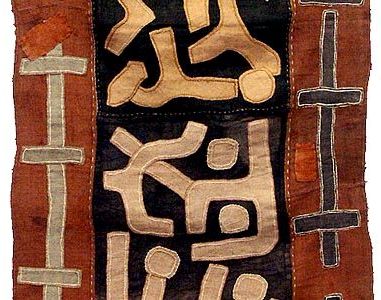

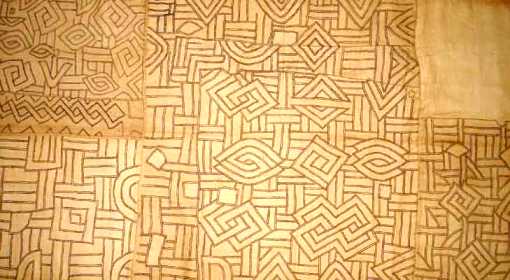

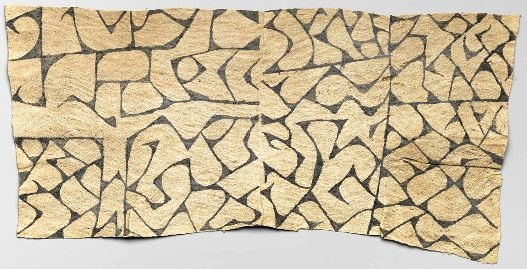

Kuba (Bushoong) cloth - from an early 20th C style, can have very graphic patterning and will always have different elements to it as it is generally made up of 3 panels. The borders can mirror each other or be asymmetrical but they are generally more complicated than the middle.

The middle panel appears abstracted with a bold arrangement of appliqued cloth in a contrasting color but the motifs appear quite randomly placed and bear names like 'tail of a dog', 'circles' and 'leaves' to correspond to the abstracted shape they represent.

Kuba cloth, Zaire

Kuba cloth, Zaire Kuba shoowa cloth

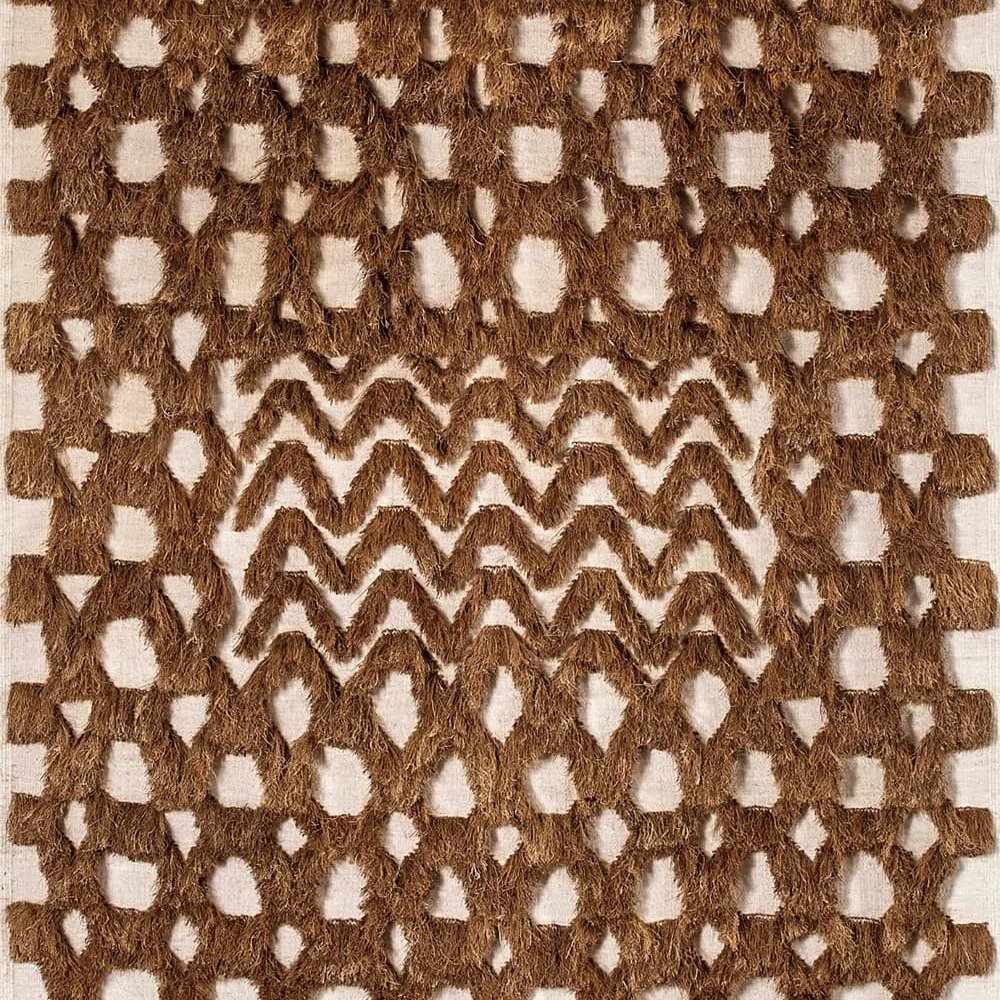

Kuba shoowa clothShoowa cloth is very structured in comparison and has dense and rhythmical patterning with overcast embroidery and cut-pile designs.

Kuba Raffia cloth is a highly patterned single color cloth made from sewn strips and squares of woven raffia cloth which has been embroidered with dyed raffia threads in all sorts of geometric shapes in interlaced and intertwined combinations.

modern raffia

modern raffiaFor further insight and information into African textiles click here

Methods of applying Pattern

There are various methods of applying and making patterns:

- Printing (stencils, stamps, sticks)

- Painting (walls, ceramics, cloth, artifacts, furniture, masks)

- Weaving (cotton, silk, man-made and natural fibres, metal)

- Sewing (embroidery, applique, objects)

- Resist (tie-dyeing, pastes, stitching)

- Carving (etched, incised)

- Sculpting (wood, clay)

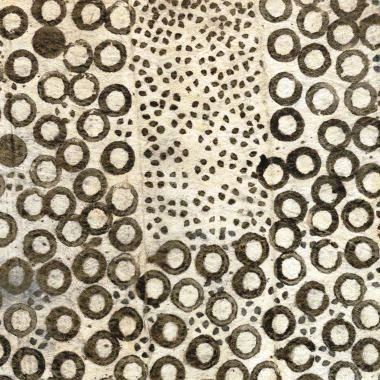

Mbuti barkcloth, (known also as Pongo cloth), is an artistic expression of the singing woman foragers of the Ituri forest in NE Zaire.

Applied in an abstract fashion to pounded bark cloth the artists paint rhythmical free-oscillating patterns using sticks and natural dye made from black carbon and Gardenia juice. The patterns are very often the same as those designs that they apply in body painting.

It seems to me to be a very fitting place to sign off on this huge page that is African Patterns as these barkcloths exhibit great spontaneity and musicality in their designs.

Abstract rhythms and deliberate contrasts are built up by leaving areas of stillness and quiet between the horizontal and longitudinal lines and the expressive free-flowing motifs that cover the cloth.

Each is a composition all of its own and it fascinates me that seemingly the most primitive works can have patterns that are enigmatic, intriguing and as reductive as the most sophisticated abstract artist who seeks to refine and define by systematic mark-making.

* Pattern making by artists/artisans/designers and architects in the contemporary African world can be viewed on this page

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.