Search this site ...

African masks

African masks are probably the most admired and well known art form of Africa for good reasons. They are both idea and form.. and while the artistry of African masks is self evident, for the people who create them, they have much deeper meaning than surface beauty.

In general, the mask form is a physical mechanism to initiate transformation whereby the wearer takes on a new entity, allowing him to have influence on the spirits to whom he is appealing to, or offering thanks.

The Western viewer is often caught off guard by the emotions that a mask can evoke.

Our intrigue can quickly be transformed to a powerful connection not often experienced in our frequently disassociated worlds. They therefore yield some notion of power which the viewer can be attracted to or repelled by. This too is despite the fact that often the viewer is studying the mask out of context and without its accompanying costume or props.

Something mystical is transferred by the nature of its function.

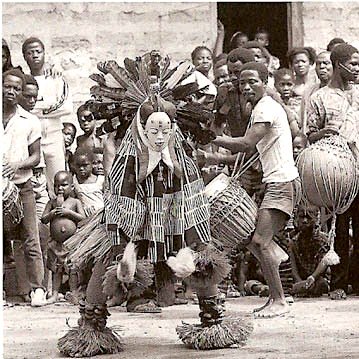

The traditional African mask is worn during celebrations, dances and festivities and ritual ceremonies commemorating social and religious events. They play a very significant spiritual and functional role in the community and often there is no distinction between social recreation and ritual celebration.

African masks are more often than not part of a unified experience, so while we may see them as sculptural forms, they can also be considered as a form of performance art. Understanding their function within this event is essential to appreciating their cultural, symbolic and aesthetic significance. They are often used in dance ceremonies to make the connection between the human world and the spirit world. Masquerades carry great religious and cultural significance for participants including the enthralled and connected audience.

The African mask is a dramatic device enabling performers to stand apart from their everyday role in society and wearers are often chosen for special characteristics or qualities they have attained or been initiated into.

African masks are in high demand from art collectors and museums the world over are reworking their archival collections to present masks in a new and vibrant format which, more often than not, focus on the beauty and variety of form of the sculptured piece.

Seeing a row of African masks from different tribal areas can show up all the contrasts of form, shape, colour, design, patterning and adornment which exist and suggest the dazzling range of formal possibilities achieved by African sculptors.

But... lose the connection of a carving with its original function and it is very difficult to establish the purpose for which it is created.

Yoruba Crest mask, Longwood

Yoruba Crest mask, LongwoodMaster carvers of masks do still exist; it is a skill that earns respect within a community and a tradition that is passed down within a family through many generations.

Carvers undergo many years of specialized apprenticeship until achieving mastery of the art. It is creative work that not only employs complex craft techniques but also requires spiritual, symbolic and social knowledge. The aura and presence of masks can put them among the most charismatic of any sculptures ever produced and the sense of play in some of the masquerade masks make them some of humanity's richest and most vibrant visual creations.

African masks are worn in three ways:

- Vertically covering the face

- As helmets, encasing the entire head

- As a crest, resting upon the head which is commonly covered by material or fibre to continue the disguise

A mask used for spiritual purposes can often only be worn once and then thrown away or burned, once its function has been performed. An initiation mask seldom survives the ceremony.

Imagine how many art pieces have been lost to the world!

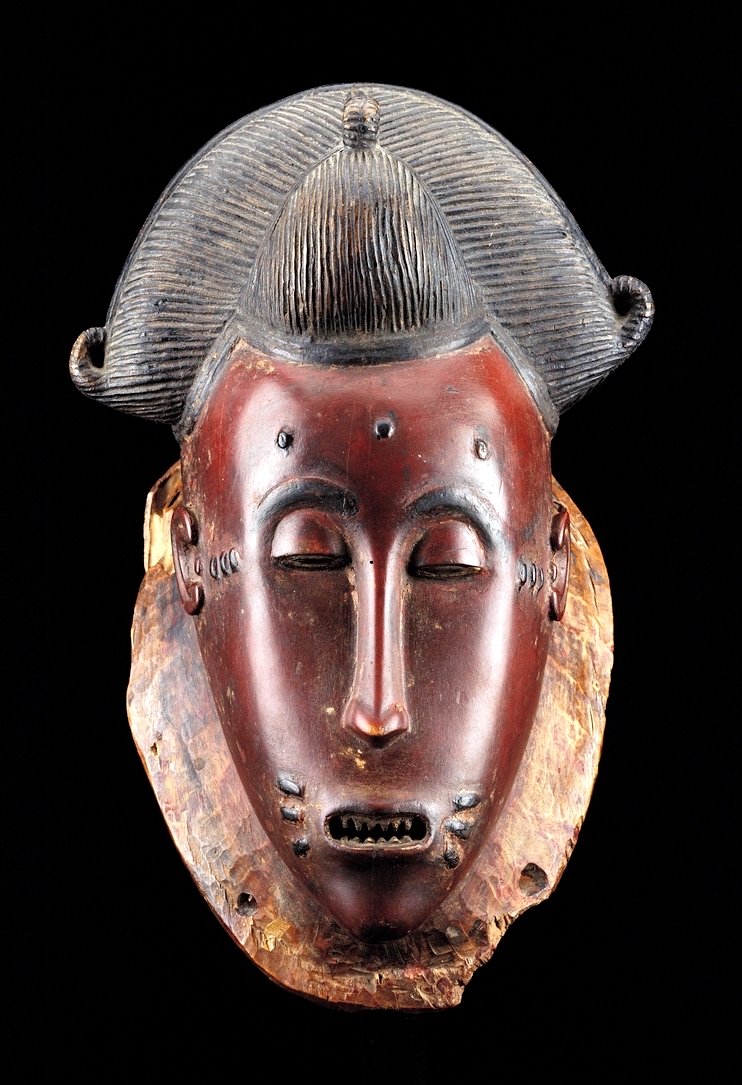

Face Mask, Senufo, Cote d'Ivoire, 19th-mid 20th C, Met Museum

Face Mask, Senufo, Cote d'Ivoire, 19th-mid 20th C, Met MuseumFor the African artist, the purpose of creating the mask was achieved once the ritual performance was over. There was no attachment to the piece but the skill and the experience is carried forward and handed down the line of descendants.

The viewing of a mask or ceremonial events can also often be restricted to certain peoples or places; there is a lot of tradition and taboo surrounding this art form. In many instances masquerades are forbidden to be seen by certain members of the community.

Materials used:

African masks are primarily carved from wood but can also be made from terra-cotta, glazed pottery, bronze, brass, copper, ivory or leather.

They are adorned and decorated with all manner of things. Cloth, raffia, plant fibers, shells, beads, kaolin, nails, colored glass, found objects like porcupine quills and other natural objects like feathers and horns.

The mask below is from the Komo or Koma Power Association and is made from wood, bird skull, quills, horns, cotton and sacrificial materials.

The elements are chosen for their metaphorical associations since they provide animals with power and protection while the animals themselves hold symbolic value in Bamana culture. The mask is further enhanced by the application of ritual substances formed with the collection of earth, sacrificial animal blood and medicinal plants.

The headdress is worn in dramatic performances that serve as a focal point of Komo society meetings and is explicitly about harnessing the forces of untamed nature.

Ceremonies

In rituals, African masks represent deities, mythological beasts and gods; metaphors for good and evil, the dead, animals, nature and any other force that is considered more powerful than man himself. A mask can function as a receptacle for prayer and appeal to the Gods for benevolence and appeasement or on the other end of the scale, power and bravery in battle.

Some of the rituals performed are for...

- Initiation into manhood/ womanhood/adulthood

- Circumcision

- Fertility

- Hunting preparation

- War preparation

- To stop destruction/invasion by human or natural forms/protection

- Witchcraft or magical rites

- Expulsion of bad spirits, village purification, execution of criminals

Rituals

African masks are generally representative of some sort of spirit and the spirit is believe to inhabit and possess the dancer as they take part in the performance.

Music (primarily drums), dance, song and prayer are all tools used to induce a state of trance by which this transformation can occur. Some of the spirits these masks evoke are represented in mask depicting women, royalty and animals.

A translator who is often a wise being who holds status within the community helps with the communication to the ancestors and the translation of the messages received, deciphering the groans and utterances of the dancer.

Celebratory

These are performed with great vigour and spectacle and the African mask is part of an elaborate theatrical event, a masquerade with costumes and props created to enthrall and entertain.

Festima, The International Festival of Masks and Arts, is held every two years. Traditionally the festival starts with the frantic parade of dancing masks. Numerous troupes from Burkina Faso, The Ivory Coast, Benin, Gambia, Togo, Senegal, and Mali come to participate in this very exciting event.

Some of the celebrations occur around...

- Burials

- Crop harvesting

- Abundance and prosperity

- Market day festivals

- Post hunt gratitude

- Post war victory

- Consulting the oracles

- Resolving of disputes

- Storytelling, expressing social expectations and conventions

- Commemorative occasions

- Rejoicing

Tribal masks

African tribal masks have a known history as far back as the stone age. For thousands of years, rituals and ceremonies were an integral part of community life. Unfortunately, these days it is less so and since many tribes have lost their cultural identity through tribal dispersement and fragmentation for various reasons, authentic masking ceremonies no longer occur in many parts of Africa.

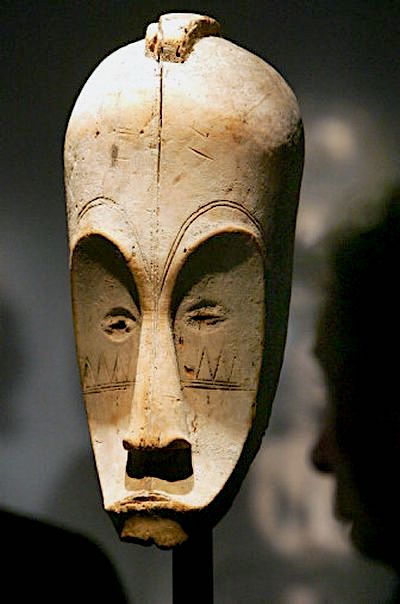

A mask like this represents the Guro conception of idealized feminine beauty and were used in Poro society dances to provide an example of how a proper Guro woman should behave. Today they are primarily used in village entertainment festivals.

There are very specific masks for very specific ceremonies which have their own function and meaning. To study all these would take a lifetime!

However, there are some prominent tribes and communities to whom masks and mask ceremonies have been a significant form of societal life and historically have defined their culture.

Some of these are listed below:

- Bwa, Mossi and Nuna of Burkina Faso

- Dan of Liberia and Ivory Coast

- Dogon and Bamana of Mali

- Fang (Punu) and Kota of Gabon

- Yorubo, Nubo, Igbo and Edo of Nigeria

- Senufo and Grebo, Baule (Guro) and Ligbi (Koulango) of Ivory Coast

- Temne, Gola and Sande (Sowei) of Sierra Leone

- Bambara of Mali

- Luba (Lulua) Songye, Teke, Goma, Lulua, Hemba and Kuba of Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)

- Chokwe of Zambia and Angola Makonde of N Mozambique

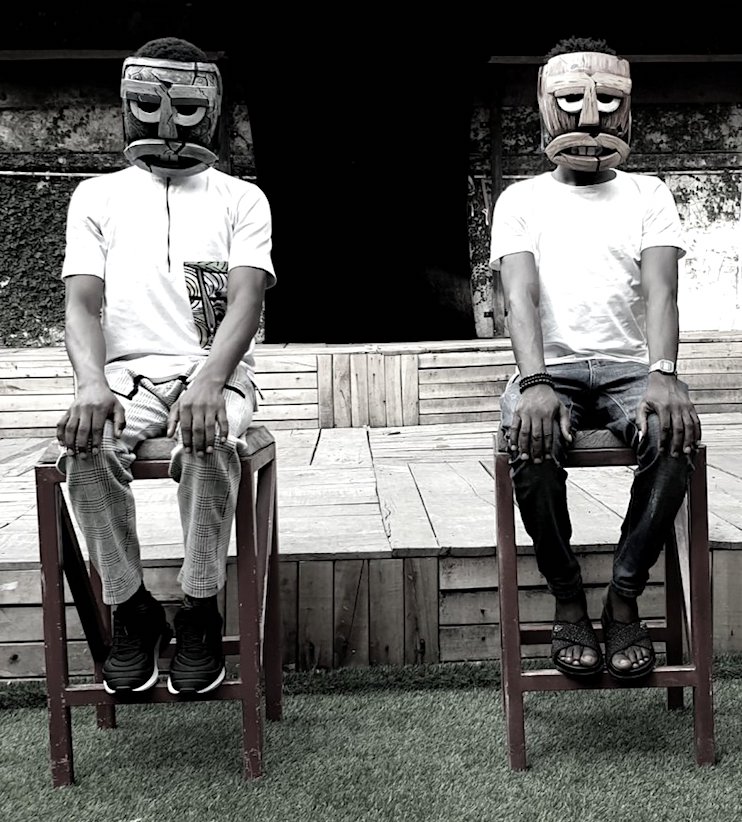

Contemporary Art Mask

Many contemporary artists in Africa are reclaiming masks and masquerades as a serious art form that collectors around the world see as an emerging opportunity. Many innovative and provocative works cover all sorts of issues like race, gender inequality, government corruption, comments on societies and limits of understanding, environment, sexuality and queerness.

Romauld Hazoume b 1962 in Porto Nova, Benin

Hazoume is essentially a brilliantly inventive assemblagist who is committed to carrying African art traditions forward while finding a new way to portray the dilemmas currently assuaging the African continent. He reworks what is sent by the West in terms of throwaway consumerables and delivers them back in a confrontational art form.

In the mid-1980's he began sculptural experiments with black jerry cans which are carried in great clusters on the back of bicycles and motorbikes in his home country. They are often the cause of fatal explosions since they are expanded and thereby weakened over heat to obtain more capacity. Romauld has used these cans as a powerful metaphor of slave repression, pushed to extreme before breaking point.

His Masks Collection transforms salvaged materials and industrial waste into spiritual objects. They are incredibly effective in conveying the same sense of power we see in traditional African masks with a sense of foreboding and a slightly confrontational aspect.

Hazoume, 'Blue Oil Head'

Hazoume, 'Blue Oil Head'Unlike traditional African masks which take on identities, these masks each have their own personalities and characters; they can be war-like, comical, animalistic, self portrait but the central theme is that their core is made from plastic fuel canisters, a symbol of negotiation, corruption and mis-use of power in Africa. (Dealing in fuel often involves illegal cross border smuggling).

The handle becomes a nose and the gaping snout and sculpted panels suggest facial features. Adornment can be found anywhere from industrial waste to found natural items like porcupine quills.

His work is reflective of an enduring African cultural art form that can be seen in the works of Joseph-Francis Sumegne, Calixte Dakpogan from Benin and Dilomprizulike of Nigeria among many other artists who work with found objects.

Joseph-Francis Sumegne b 1951, Cameroon

Sumegne's sculptures are a true reformation of waste and rejects that are made mainly from wire/scrap iron and material that he has collected and stored in his workplace. For me they exhibit the same qualities as African masks do, slightly sinister and enigmatic but with strong bearing and form.

The heart of Sumegne's work is the "9 Notables", a collection of giant mannequins that began to be created in 1988. They challenge modern-day societies in Cameroon, drawing attention to the rupture between traditional Bamileke culture and today's contemporary one.

Ngima Thogo b Nairobi, Kenya

Ngima Thogo is a self-taught, Kenyan digital artist who lives and works in Nairobi, the capital.

He draws inspiration from African tribal masks and skin scarification used by various cultures as forms of identity. A former photographer he blends the 2 art forms to create these art pieces which combine photographed human bodies with digitalized facial masks.

In an interview with Okay Africa the artist had this to say about his inspiration... "My influence compass points are in many aspects, from the intercultural heritage of traditional African face masks to scarification identity marks of various cultures. I also find joy in little details of the situations I encounter daily. I’ll get inspired by other individuals in my field that I look up to".

Yussuff Aina Abogunde, Nigeria

"Masks are both a traditional and essential form within African art that people tend to associate with traditional events, but I want to break that mold. I want to make a new African aesthetic and for masks to be part of that conversation," said Yusuff Aina Abogunde, a Nigerian artist who has taken the revival of masks in African art and Afrofuturism one step further than most.

Nick Cave b 1959, Missouri, USA

Nick Cave Soundsuits are reminiscent of African, Caribbean and other ceremonial ensembles. First created in 1992 as an artful but provoking response to the Rodney King beating. His first suits were created from twigs that initially took form as sculpture but ended up being ultimately a garment that moved when worn... 'soundsuits' were born.

His work explores issues of transformation, myths, rituals and identity.

He has undoubtedly been influenced by tribal masquerades and his 'sound suit' installations and accompanying videos are very reminiscent of all that those ceremonies conjure up for all participants be they viewer, listener or performer.

Cave has created more than 500 soundsuits since the 1990's, crafted mostly from discarded materials and thrift-store finds like multi-hued shaggy materials and all manner of found objects; sequins and fur, bottle caps, sticks; metal and wooden, fabric, hair, ordinary materials that he transmutes into multi-layered, mixed media sculptures.

To view more contemporary artists working with masks see this page on CAA

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.