Search this site ...

South African Rural Sculpture

Fish shaped Scraper, Thomas Kubayi, Limpopo

Fish shaped Scraper, Thomas Kubayi, LimpopoRecent History

South Africa has a rich rural carving tradition. During the 1980’s this mode of artistic expression acquired new dimensions with the emergence of rural artists who were self taught and unexposed to other influences. As a result of the isolating of black South Africans into rural community areas, the artists residing in these areas created work that was authentic and unconditioned.

It reflected their traditional values but also their own life experiences. Having had little contact with the existing South African art world, when this work did come to the attention of researchers and galleries it had a significant impact, creating quite a stir when shown at the exhibition ‘Tributaries’ in Johannesburg in 1985.

Jackson Hlungwani

Jackson Hlungwani, (1923 - 2009) was an individual who felt blessed to have what he termed 'a direct link to God'. Having found Zionism early in his life and having experienced a personal, visionary encounter with Jesus, his work was impassioned by his own spiritual experience.

Born in 1923 in the Northern Province of Venda, the son of a migrant Shangaan worker, he believed himself to exist among lesser mortals. He attached no value to acquiring the status of ‘artist’, refusing to sign his name to works or to be seduced by the lure of acclaim.

'Christ on Cross', Jackson Hlungwani Norval Foundation

'Christ on Cross', Jackson Hlungwani Norval FoundationHis complex carvings were only discovered when he was in his 60’s when he was found near Elim carving placidly under a tree by a scouting art critic and curator named Ricky Burnett in the 1980's. Here in Mbokhoto, on top of a hill, he had built the Altar of God at New Jerusalem with found wood, stones and other materials evoking a little Great Zimbabwe Ruins and celebrating his own brand of mystical and fantastical Christianity. He called it ‘The Map of Life’.

By 1989 he was fully discovered by the Johannesburg art scene but refused to conform to the expectations of the art world which proved frustrating for those trying to promote his art. His work is conceptually complex; merging religious, traditional and technical concerns.

Wooden Panel, Hlungwani

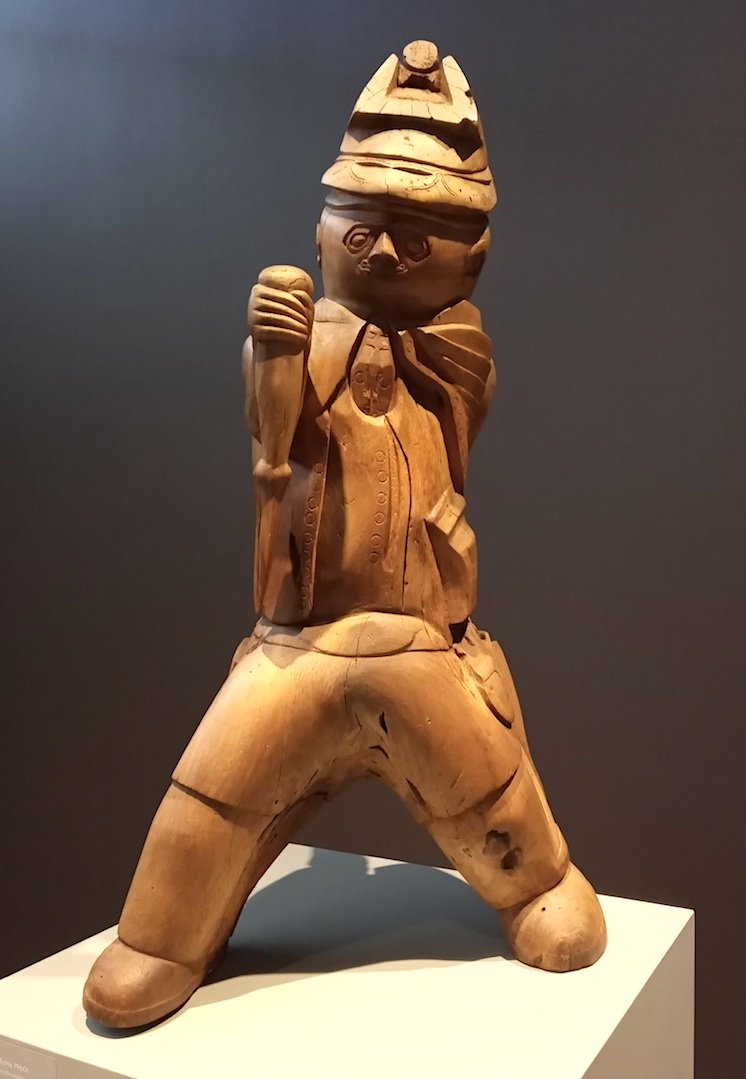

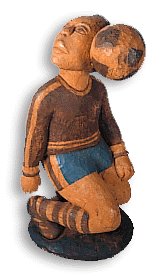

Wooden Panel, Hlungwani Wooden figure, Jackson Hlungwani

Wooden figure, Jackson HlungwaniUsing indigenous woods he approaches figurative formations with sensitivity and skill but harnesses the raw material’s innate substance so that the sculptures have a powerful presence. Some of his images like fish and crucifixes are used consistently while others have a sense of play like Jesus playing football.

Hlungwani’s art reminds us of our free will; that we have a creative spirit and can express our uniqueness through that difference.

Noria Mabasa, b 1938 - Born in Tsigalo, Venda, Mabasa has worked full time since 1976. She first modelled a small clay sculpture in 1974 of a young girl beating a drum, an image from a dream which was followed by other small girl clay figures.

While she works predominantly in clay she also uses wood and can execute any size of sculpture; whatever her dreams determine.

In the 1980’s she painted her clay figures with enamel

paint but in more recent times her figures are earthier in both subject matter

and application. When her local area achieved independence from the Government in 1979 her focus turned to making ironic social and political comments on the nepotism and corruption that was epidemic within the new authorities.

Her

wood carving on the other hand is much more rooted in her ancestry and the

transference of her dream imagery to material. It has given her an outlet to

demonstrate her full power as a carver, traditionally a male vocation.

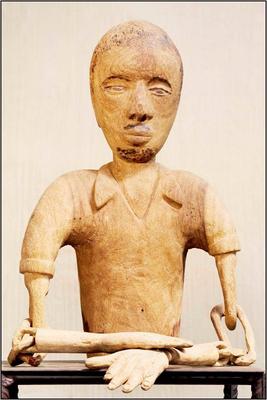

Nelson Mukhuba (1925-1987) was a fellow Venda carver who

exposed the dealer Burnett to Mabasa being hugely impressed by her abilities.

His work most exemplifies the clash between first and third world cultures and unfortunately Mukhaba became a victim of personal destabilisation. Angry at the art establishment for taking advantage of him, he took his own life and that of his family in a ritual killing.

He worked mainly in jacaranda and marula, also sometimes painting his figurines and stating ‘I am the doctor of wood because I can see inside the wood’. His images came from the bible, from dreams, from politics ‘Vorster’ and TV personalities, indeed a great mixture of things that reflected the two worlds he lived between eg ‘Drunk boer’, ‘Ballet Dancer.’

Dr Phuthuma Seoka (1922-1997) was another Venda individual who sculpted from his dreams ('Black Dog', 'Leopard') as well as producing political, archetypal, figures with satirical twist. Piece's such as 'Angry Boer' and 'Cross Madam' with sour aggressive faces demonstrate this work as does 'PW Botha' with his blinded glasses.

He used strong colors and decorated his pieces by burning on the natural wood.

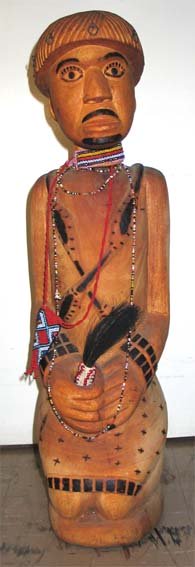

Johannes Maswanganyi, b 1948. Maswanganyi has, more than the other artists of this genre, concurrently produced two types of work that have different purposes:

Decorative, enamel painted pieces that are created for the commercial white market and those that are sangoma pieces, ‘nyamusoro dolls’ which are completed by the addition of sangoma charms. Johannes has a broad humanistic view on the world and continues to explore all sorts of new avenues of expression which include satirical portraits of political figures, and animal and biblical themes.

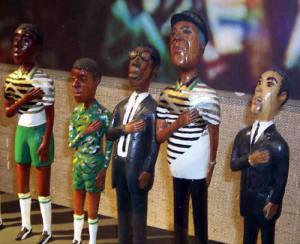

Johannes Segogela, b 1936. Segogela only became a full time artist in the 1980’s and has been represented by Goodman Gallery since 1987.

He comes from a strong tribal background but having embraced Christianity his work reflects his spiritual zeal as well as the impact of politics upon his culture.

Religious

tableaux exist alongside allegorical comments on SA society. Segogela’s figures

are slightly stiff but acutely observed and his installations reveal

sensitivity, humour and an element of irony.

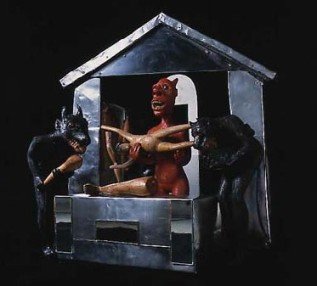

His iconic sculpture ‘Satan’s Fresh Meat Market’ is full of angels and demons and demonstrates very effectively his personal goal to ‘save the world from violence and horror’.

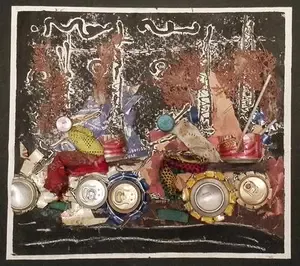

Samson Mudzunga, b 1938, Dopeni, Venda.

Mudzunga’s work was first shown in some depth at Fuba Gallery in Johannesburg in 1988.

His family lived around Lake Fundudzi in Venda province, an area which was steeped in local mythology and is a sacred site for the community. The influence of this is reflected in his figurative pieces shown in the gallery.

In the mid 1990’s he produced large drums which incorporated symbolism from his local mythology and traditional customs. These drums addressed issues of power within his community. Samson has achieved much acclaim in this last decade with his participation in both solo and group exhibitions in Africa and abroad.

Samson Mudzunga, Self Portrait

Samson Mudzunga, Self PortraitRural sculpture in South Africa is an interesting area to observe because of the dissension over whether it constitutes fine art or... craft?

The vital thing to note is that the artists, living in relative isolation, were creating to satisfy their own needs and that of their community instead of a gallery or public.

In general, sculpted pieces were not crafted for utility means, even the ladles or totem poles that are featured here were created for ceremonial purposes, part of a ritual or celebration. Sometimes just the sheer nature of the wood revealed a theme to the artist resulting in free flowing and dynamic forms. Other artists chose to represent in visual reality messages from gods or spirits, or their personal dreams or visions.

There are many other artists that could be included here, some that need mentioning are: Albert Munyai, David Murathi, Meshak Paphalalani, Hendrik Nekhofhe.

Contemporary Rural Sculpture

Two artists have made their mark in recent years continuing the tradition of rural sculpture but making new comment with their art. Phula Richard Chauke and Philip Lice Rikhotso are both award winning sculptors who live and work in rural Limpopo yet their art has had great impact much further afield on the contemporary art world.

Philip Lice Rikhotso was born in 1945 but only started carving some thirty years later.

He is inspired by traditional Tsonga and Shangaan folk stories and legends, his work often illustrating tales of witchcraft explaining the carved figures of people metamorphosing into animals and birds or even anthills.

His signature style includes common features of figures with large teeth, oversized eyes and hands covering the crotch area concealing the creature’s sexuality, modesty normally prevails. (Not sure about figure on right below!) Raw wood often shows through; figures are partially painted for emphasis.

Phula

Richard Chauke

b 1979, also from Giyani, Limpopo province has a number of subjects that make

up his social comment and are keenly and wittily observed:

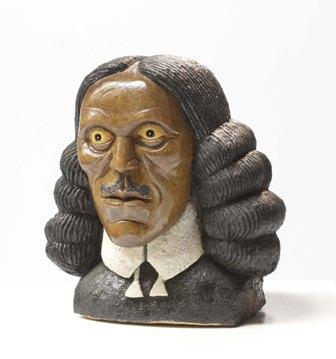

- Politicians driving in their cars, personages of historical or religious stature like Van Riebeeck, Shakespeare, Desmond Tutu, or Emperor Selassie.

- Women are often carved to represent the circle of life passed on for generations; a mother, a sangoma and a sister enduring and repeating the patterns of existence.

This

portrait of Van Riebeck is startling and unnerving, the explorer’s skin tone

dark and disturbing, his countenance shocked; the whole effect understatedly

delivered as a political comment on the impact of western civilization on

Africa.

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.