Search this site ...

Bogolan mudcloth

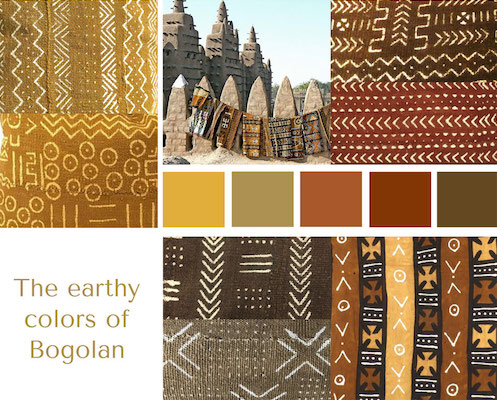

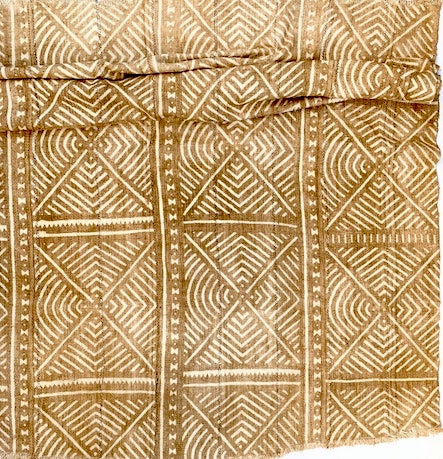

The Malian Bogolan is one of the world's most recognized and distinctive, handcrafted African textiles. Strikingly dramatic in its strong, contrasting tones of cream and ochre through to black/brown or indigo blue, the cloth has many applications and uses.

More recently, it has been embraced as a symbol of Malian cultural identity.

Termed Bogalanfini (Bambara term) or Bogolan (modern terminology for a contemporary cloth), this textile is a handmade, Malian, cotton fabric which has traditionally been dyed with fermented mud in a painstakingly long and complex process. The cloth was made traditionally by the Bamana who live to the east and west of Bamako, but the best cloth comes from the Beledougou area where it is thought the cloth originated from as early as the 12th Century.

The centre of production is San and the highest quality cloth can be found here, woven by the menfolk into strips of narrow cloth which are then stitched and dyed by the women of the town. Decoration takes place by either males or females and the whole process can take weeks to complete. Generally, 6 bands of handwoven, plain cloth are sewn together, selvedge to selvedge, to produce the larger item known as bogalanfini cloth (5 if there are borders).

This cloth was a major element of life; often incorporated in milestones and sacred events. Historically worn by tribal women as a wraparound item of apparel, like a skirt or shawl, it signified important, transitional events like after excision, pre-marriage, childbirth and finally a burial shroud.

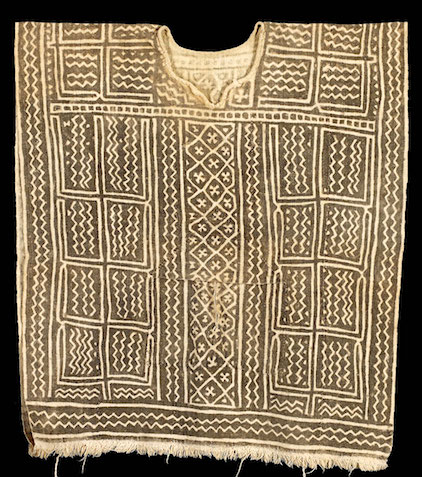

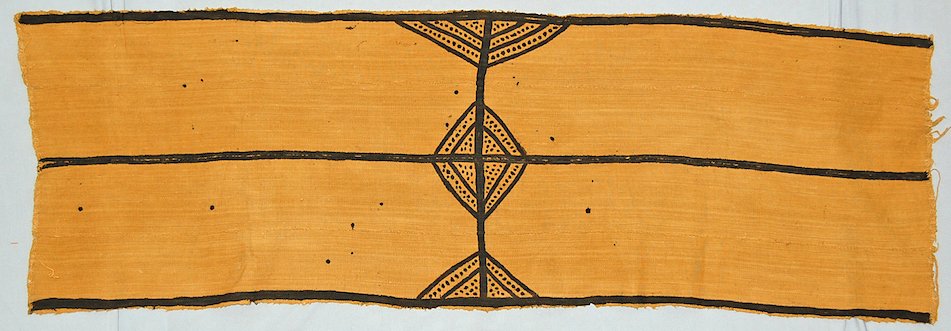

It was also worn by men as a hunting tunic or shirt such as this historical item featured above. Sometimes these tunics would be dyed red as camouflage in desert areas. Amulets and leather accessories would also be worn for good luck.

History of Bogolan cloths

Bogolanfini etymological roots are Bambara, the language spoken by the Bamana people of Mali and it is derived from 3 words.. 'logo' meaning mud/earth, 'lan' meaning by means of and 'fini' meaning cloth. Its an ancient tradition but the fragile and perishable nature of the cloth means it is virtually impossible to trace its origins.

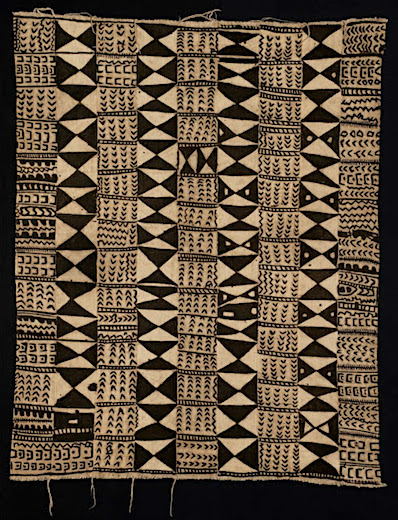

However, many beautiful antique examples of mud cloth can be found in museums throughout the world. This cloth below resides in the British Museum and was worn by women following excision and during the final ceremonial after which a girl goes to her husband's village.

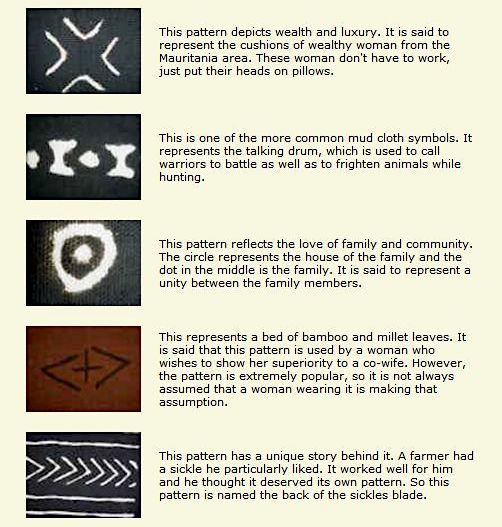

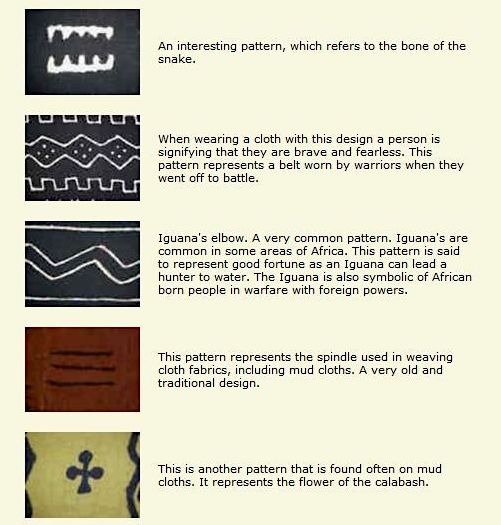

Designs would be aligned (horizontal, vertical, borders) according to their end usage. The designs go beyond aesthetics being traditionally based on cultural symbols and patterns and are full of meaning making reference to animals, religion, cultural and historical events, tribal stories and mythologies.

With each cloth's unique message and the hand rendered process, no two pieces of cloth can ever be identical: There are so many different aspects to the craft of producing this textile.

As many African countries gained their independence, national pride in traditional crafts grew significantly. Social and political developments in the USA caused an interest in African textiles and 'back to roots' cultural identity.

Popularity of these textiles even extended to fashion and in 1979 a young Malian designer Chris Say-dou (the father of African fashion) included bogolan wraps in his collection in Paris. From then on factories and commercial ventures began to be set up in Mali and these cloths were produced on a larger scale for a more materialistic use.

Process of making Bogolanfini

Spinning, weaving and sewing are gender specific tasks. Women hand spin yarn of locally grown cotton while menfolk continue the process by weaving the undyed yarn into long but narrow strips using a hand held, double heddle loom. They then sew the strips together, selvedge to selvedge, to produce large cloths which can be used for garments for either sexes.

This final result is called finimougou which is prewashed and shrunk for use in either its uncolored state or taken to be dyed in the elaborate process that characterizes bogalanfini.

Roots for Bogolanfini dyeing, W Africa

Roots for Bogolanfini dyeing, W AfricaThis fabric will be soaked in brown liquid which is colored by the leaves from the n'gallama tree giving the cloth a distinctive strong yellow base.

The yellow color does not appear in the finished article but it significantly contributes to the process, acting as a fixative for the colors to come... the tannic acid in the tea combines with the iron oxide in the mud to create the familiar dark brown/black background color we associate with bogolanfini.

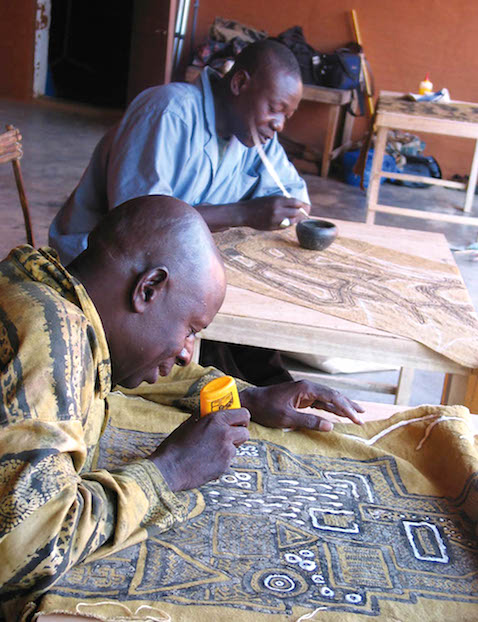

Once the cloth is dry the patterns are drawn on to the fabric with a pointed iron spatula, stick or quill and the negative space is covered with fermented mud until it turns grey.

The design will be light (yellow) against the dark background. Then when the mud is dry, it will be washed off and the process repeated again and again until the desired depth of tone is achieved in the background.

Repeat process of painting with mud

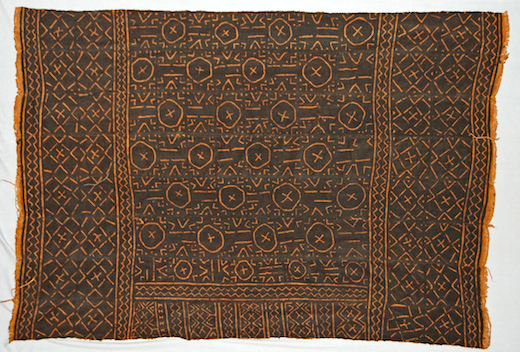

Repeat process of painting with mudSome tribes prefer terracotta or red tones and the women use a mixture of different leaves, roots and bark to get the rich, burnt-earth to orange tones.

The remaining yellow places are then bleached to get the fabric back to its original, undyed color. These areas are painted with a substance made of ground peanuts, caustic soda, millet bran and water which turns these places a light brown. When washed out a week or so later, the once yellow design will emerge bleached and pure white, a dramatic contrast to the dark ground.

Modern versions of African mud cloth involve a completely different type of process. The cloth is dyed with a tree leaf and bark solution from the M'Peku tree creating deep russet tones.

Black and white designs can be painted on top and sometimes a stencil is even used, either for the mud pattern or the paint pattern.

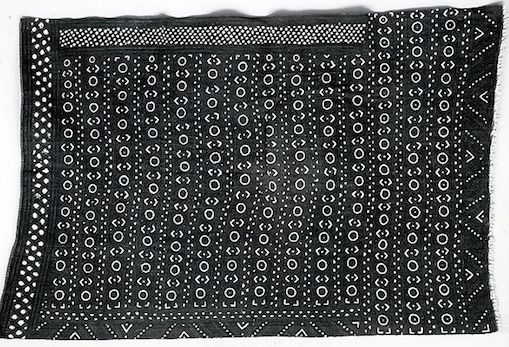

In this cloth below, the dark tannins that create the brown/black dye for the background have been replaced by indigo dye. The same bleaching process happens to create the light design.

Vintage indigo Bogolan mudcloth, Dogon

Vintage indigo Bogolan mudcloth, DogonMeaning of Bogolanfini, its symbols, patterns and colors

There is a symbolic language in these designs and the meaning of these symbols is closely guarded by tribal womenfolk. This knowledge gives them prestige in their societies. The designs are meant to be imbued with magical and therapeutic properties, giving them a life-force of their own, called nyama which holds sacred powers of protection.

Some women have their own concoctions, using different plant species to make up the dyes which are used; essentially white, red (terracotta) and black.

- White bogolanfini is associated with both death and purity.. brides wear these wraps during their wedding ceremony but white is also used as a shroud for both genders.

- Red bogolanfini is worn by young women during excision and the following period of isolation.

- Black bogolanfini is the most common colored cloth and is used for more general wear.

Bogolanfini is a very distinctive textile and very 'African' in flavor. Strong geometric or natural patterns, earthy colors like ochre, terra-cotta and charcoal, thick, robust and handwoven cotton fabric sewed together with manually bound seams... it speaks of heritage, culture and tradition.

The symbols used in the designs of these beautiful cloths can be interpreted according to knowledge passed through the generations, mother to daughter. The main ones can be seen in the charts below but there are many more and as time passes, new ones are introduced, sometimes for aesthetics alone.

Cultural tourism has become a pillar of many local communities either selling or making bogolan cloths since the mid 2000's when UNESCO declared many new cultural sites in Mali.

Modern day Bogolan

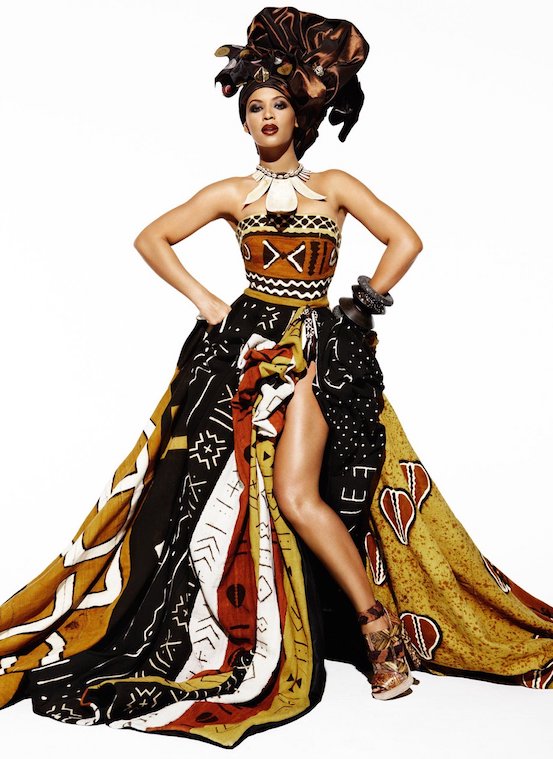

These days, Bogolan cloths are widely exported from Mali and used in fashion, upholstery, interiors and decoration. Design and color wise, the fabric has widespread appeal and fits into many applications in the home decor and fashion world.

Of course, the authentic and traditional version is still produced and there is growing concern for how the demand for a more commercial version will affect the future of the production of these traditional cloths. Especially as those tribal folk that have the knowledge are declining in numbers. On the other hand opening up the process to accommodate a wider market has had significant impact on the spread of the appreciation of the fabric and makes heritage more relevant to today's society.

Decor -

Bogolan scatter cushions

Bogolan scatter cushionsScatter cushions, throws, table linen, bedspreads, upholstery... bogolan cloths can be applied to many decor options. An undyed ground with a mono print of a less complicated and repetitive pattern is particularly appealing for a more contemporary look for upholstery and bed throws. The natural hand sewn seams are still prevalent giving it a degree of authenticity that modern consumers like.

Mono-printed Bogolan wrapper with red pattern

Mono-printed Bogolan wrapper with red patternHand-printed contemporary bogolan cloths bear little in common with traditional bogolanfini but textiles such as the one above from Morissey Fabrics have all the attractive qualities of the original; simple design features in complex combinations.

Fashion -

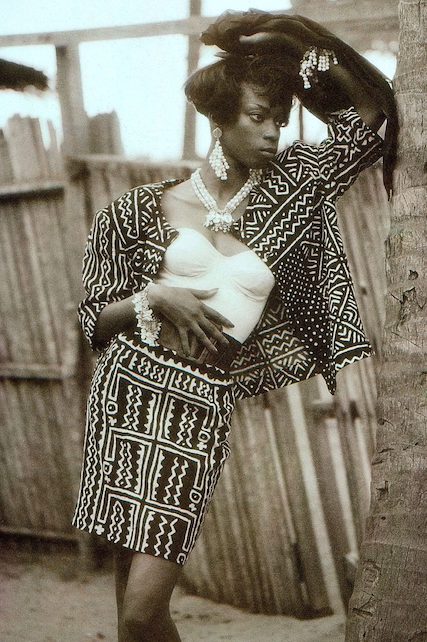

Considered by some to be the founder of African design, Malian Chris Seydou (1949-1994) took bogalanfini to the catwalk in the 80's and early 90's but had to re-design the patterns into a repeat form that suited his clothes.

This was the start of simplifying the cloth which he did in Abidjan, Ivory Coast in 1981, firstly by commissioning hand printed fabrics and then by introducing factories that could produce what he needed to make his signature cropped jackets, mini skirts, hats and coats as seen below...

These days it is used in a much more flamboyant way with bigger repeat patterns or even modern interpretations of the printed patterns. It is commonly applied to the manufacture of ethnic styled handbags, luggage, jackets and many more items of apparel.

Bogolan designs and prints are perfect for handbags... mixed with leather, as above, this is an extremely attractive and durable, classic fashion item.

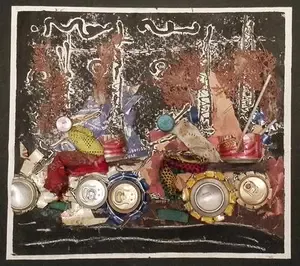

Contemporary Art using Bogolan cloth as inspiration

The Bogolan Kasobane Group

6 artists, recently graduated from the National Institute of Art, Bamako formed this group in 1978. It still exists today with the same members but for one (Kandioura Coulibaly) who died in 2015. Their newest member is a woman, Nene Thiam.

Their common goal was, and still is, to innovate and promote the art of making bogolan cloth in Mali and the rest of the world. They have exhibited widely, promoting their contemporary pieces as well as showing the origins of bogalanfini. Their works are layered with meaning and manage to raise the basic materials used in the craft into something contemporary and significant in its own right.

They are also very interested in the cloth being used for non-traditional, combined purposes; like using bogolan fabric to make up boubous, the traditional, long garment with wide sleeves worn by Malian males. Usually its embroidered but with Group Kasobane, the robe is given a very different take... an elaboration of tradition in their attempt to preserve their heritage.

They also make costumes and sets for theatre and film using modern bogolan cloths.

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.